Warning: This text is uninformed opinion.

But that’s fine. Uninformed opinion is the sacred text of our culture. Do you want proof that our culture worships opinion, provided that opinion is completely disconnected from knowledge? Here are three:

- Proof 1: Blogs.

- Proof 2: Dr. Phil.

- Proof 3: Rush Limbaugh’s call-in show In fact, any radio call-in show. Not the hosts of talk radio—the callers. The guy at the end of the telephone line is given more air time than all of our elders, all our philosophers, and all our religious visionaries combined. All of that wisdom is nothing when stacked up against some uninformed crank just knowledgeable enough to dial a telephone.

I am one of those uninformed cranks.

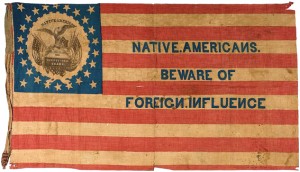

The glorification of ignorance is not new. The Know-Nothings flourished in the US in the 1850s. They championed the rights of white, Protestants against the tide of urban immigrants (mainly Catholic) who were flooding into the cities along the eastern seaboard. The Know-Nothings were the most successful third-party political movement in US history.

The glorification of ignorance is not new. The Know-Nothings flourished in the US in the 1850s. They championed the rights of white, Protestants against the tide of urban immigrants (mainly Catholic) who were flooding into the cities along the eastern seaboard. The Know-Nothings were the most successful third-party political movement in US history.

The themes they raised the anger of the most politically powerful against the least powerful, the attack against foreign contamination, the struggle with ethnic difference, the championing of the pastoral against the urban these exact themes will come up again as we attempt to understand the nature of Winnipeg.

So I feel entirely comfortable being ignorant. I’m in a long and noble tradition.

3 Questions

- What is a city?

- What is this city?

- How can this city be changed?

It is ridiculous to take on these sorts of questions. They are too big. Too old-fashioned. Asking these questions exposes me as naive. That third question it makes me do-gooder—a Know Nothing and a do-gooder.

Fine. Chances are, if you’re reading this, you’re a do-gooder too. My experience is, any text/monologue/discussion about Winnipeg turns almost immediately to a debate on how to make this place better. For an urban planner, “making this city better” might mean “making it more liveable”. For a politician, it might mean “fixing downtown” or “filling the potholes”. For a developer, it might be a shiny new suburb.

Whatever the meaning, the language we use is the same: “Make this city better.” So far as I can tell, this urge to improvement is just assumed. So we should ask: Where did this urge to make the city better come from?

Whatever the meaning, the language we use is the same: “Make this city better.” So far as I can tell, this urge to improvement is just assumed. So we should ask: Where did this urge to make the city better come from?

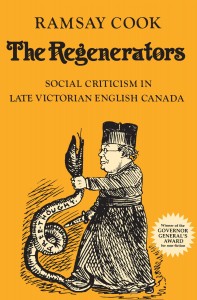

In Canada, at least, it has a particular origin, in a movement that flowered in Toronto about 100 years ago—the Regenerators. The Regenerators began as a religious impulse as a desire to make Christianity relevant to the lives of Canadians. It evolved over roughly 30 years from 1890 to 1920 into a consensus on the nature and value of a secular, urban society.

The Regenerators began as religious reformers, but ended up as secular champions of what you might call “the urban belief”. In the urban belief, the city is secular/pluralist/progressive/good.

The Regenerators began as religious reformers, but ended up as secular champions of what you might call “the urban belief”. In the urban belief, the city is secular/pluralist/progressive/good.

This belief helped underpin the Social Gospel and the CCF. It echoes in the Canadian utopia of Expo 67. The urban belief reverberates today in the livable city movement. Jane Jacobs was an incarnation of the Regenerators.

For Winnipeg, much of our public conversation can be framed as a debate between the Know Nothings and the Regenerators. If you’re a planner, an architect, a politician, an city activist, a lot of your time will be spent caught in between these two forces.

1. What is a city?

“…coded macro-ambiental features, such as, in architecture, a house, a temple, a square, a street.” Umberto Eco, A Theory of Semiotics (1976).

“…certain urbanists, or certain of those investigators who are studying urban planning, are obliged to note that, in certain cases, there exists a conflict between the functionalism of a part of the city, let us say of a neighbourhood or a district, and what I should call its semantic content (its semantic power).” “There also exists a conflict between signification and that calculating reason which wants all the elements of a city to be uniformly recuperated by planning, whereas it is increasingly obvious that a city is a fabric formed not of equal elements whose functions can be inventories, but of strong elements and of neutral elements, or else, as linguistics tells us, of marked elements and non-marked elements…” Roland Barthes, “Semiology and Urbanism” (1967).

Usually, we talk about a city any city in two ways—as a noun, and as a verb.

The City as Noun: Buildings. Houses. Streets. A traffic corridor. The core area. The city as stuff.

And there’s The City as Verb: A city is “where things happen”, where human action occurs. Buy. Sell. Build. Live. Commute. Enjoy.

Both are inadequate. It is more useful to see a city, not as a particular part of language, but as a specific kind of language.

The city-as-code crowd are agnostics; they acknowledge Austin’s existence, but little else. Jacques Derrida undertakes a summary of Austin in “Signature Evénement Contexte” (1972), but misses a lot.

J. L. Austin, How To Do Things With Words (1955).

Grammarians will hear echoes of John Searle’s speech act “theory” (Speech Acts, 1969) and Adolf Reinach’s, “Die apriorischen Grundlagen des bürgerlichen Rechtes” (1913). But that’s for another day.

Of course, the idea of a city as a linguistic structure isn’t new at all. Umberto Eco. Roland Barthes. Almost any architectural theorist since 1970. They say language is a carrier of meaning; a code. Then they say architecture is a language. Then they try to decode that language, asking: What messages does this architecture contain?

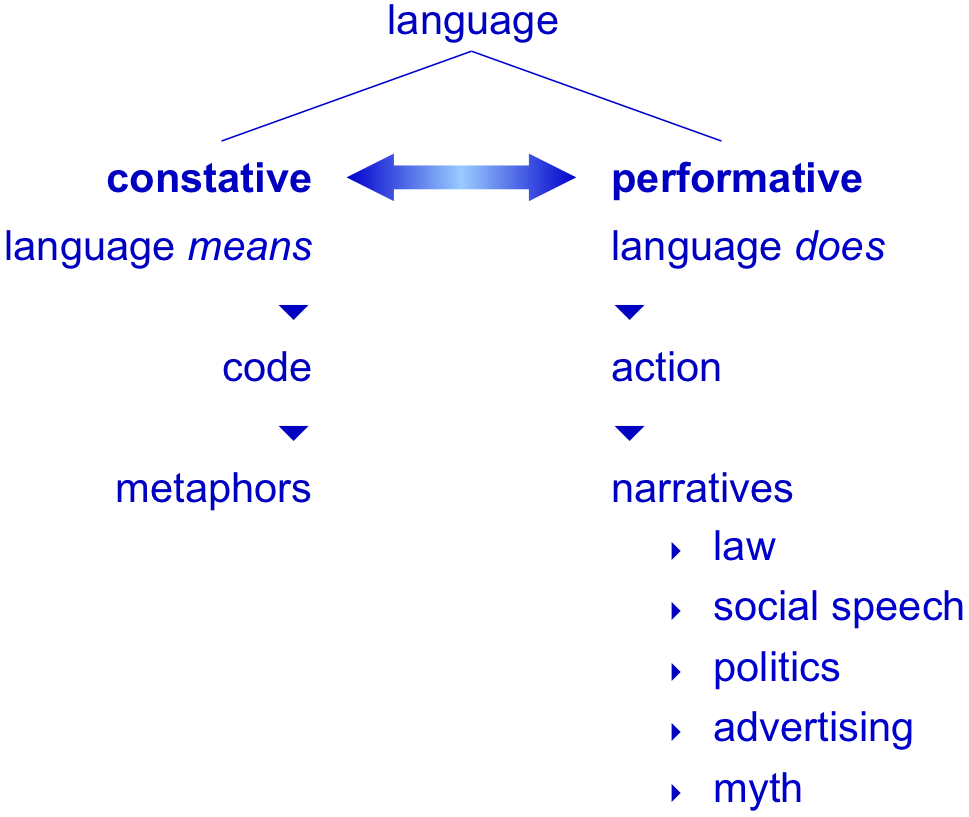

The city-as-code crowd make a key mistake: They ignore J. L. Austin. Austin proposed a distinction between constative and performative language. Constative language means something; performative language does something.

Constative language is symbolic, with a non-linguistic referent. “I bought this jacket at Value Village.” The words are signs of my action, and can be judged as resting somewhere on the line from true to false (or, if you prefer, between coherent and incoherent).

Constative language is symbolic, with a non-linguistic referent. “I bought this jacket at Value Village.” The words are signs of my action, and can be judged as resting somewhere on the line from true to false (or, if you prefer, between coherent and incoherent).

Contracts, social exchange, power relationships, liturgy, the language of advertising—all performative. “You should go to Value Village and buy a jacket too.” The words intend to convince you to action. Judging these words as true or false is like judging a book by its cover. Performative language does not function to describe a world, but to create or alter it.

Narrative is pure performative. Story is not description; it conjures a world and its inhabitants and inserts them into your imagination. And it’s this language—language not as code but as action—that I think is useful for analyzing a city

A city is an act of storytelling or, more accurately, multiple acts of story-telling. Some of these stories “work”—that is, they take hold in the minds of the citizens and become enduring narratives; they become myths.

Myths are not a way of avoiding reality. They are an effective way of facing reality, grappling with it, and changing it. To understand urban macro issues (How does a city grow or decline?) or micro issues (How does this particular building get built? How does that particular capital expenditure line get written into a city budget? Why was this variance granted and that one declined.) you need only understand its enduring narratives. You have to know a city’s urban mythology. Not in general; in particular.

A Detour

But just before we look at what Winnipeg’s particular myths, let’s detour a bit and ask “In what medium is that story told?”

For most of the past century, the dominant medium for the mythology of cities in the broader culture has been movies.

Two examples.

Casablanca

The opening of Casablanca is an explicit creation of a city.

[insert video]

Julius J. Epstein et al., Casablanca (1942).

This Casablanca is a complete invention. There never was a wave a refugees coming down from Europe, across the Mediterranean, across North Africa, and into Casablanca. Casablanca never served as a limbo for people fleeing the Nazis. All of that was made up.

The effects of this narrative fiction aren’t confined to this movie. It is performative. When we see it, the movie inserts its “Casablanca” into our imaginations. From then on, whenever we speak the word “Casablanca”, it conjures the image up in our minds, even though there is a physical, competing Casablanca out there. This conjured image acts as a competitor with the physical reality of that particular city.

This power of narrative myths to overwhelm reality is something we’ll see again when we attempt to understand Winnipeg.

New York

There are dozens of movies that insert “New York” into our minds. To take only two:

Manhattan

[“…for him, the city was a metaphor”]

Woody Allen, Manhattan (1979).

Allen creates New York as an Eden, a paradise for rich, unhappy people.

Or New York as Hell

Batman

[…from bat-plane shooting out of clouds… …to Joker with arms stretched…]

Sam Hamm and Warren Skaaren, Batman (1989).

Batman is a pure Gnostic melodrama. But who is good and who is bad is completely arbitrary roles assigned by the storyteller. The Joker stands in a Christ-pose, under attack by a sinister force. The storyteller has decided to make this black good and this white evil.

This quality of myths—characters and meanings transform while the narrative endures— we’ll find it again in the narratives we’ve constructed about Winnipeg.

True?

Let’s talk—even if only briefly—about truth. We have “myths” and we have “facts”. (Pretend it’s that simple.) In some cases, the two are quite tightly tied together, so we say, “This myth is accurate.” In other cases, there is almost no connection between fact and myth, and we say, “This myth is false.”

Too simple.

Myth is performative language. It is not enough to ask: Is this myth “accurate” or “inaccurate”? Instead: Is this myth “powerful” or “weak”?

Ask: What does this myth do? Not in the past, but in the present. Are those actions toxic? Healthy?

The Winnipeg Medium

Of course, in Winnipeg, we don’t use the medium of movies to tell our myths. Our media are:

- words

- the speeches of leaders

- boosterism

- the branding campaigns

- what we say when we show visitors around

- civic projects

- highways

- bridges

- public art

- civic buildings

2. What is this city? The Winnipeg Myths

I propose eight myths for Winnipeg:

| Red River Rebellion | 1869 | ||||

| The North End | 1900 | – | |||

| Chicago of the North | 1900 | – | 1914 | ||

| The Strike | 1919 | ||||

| The Flood | 1950 | ||||

| Unicity | 1960 | – | 1970 | ||

| The Forks | 1987 | – | |||

| The Harper Shooting | 1988 |

It’s striking that we have so much narrative; not every city does. Our city has soul; the depth of that soul is measured in the number and richness of these narratives.

I’m not going to do them in order. We’re after themes, not chronology.

Chicago of the North

The civic leadership who coined this term 100 years ago were trying to conjure up a bustling, urban centre. The Chicago-of-the-North narrative elements are:

- urban—but not a European urban, an American urban

- an external reference point—another city in another country as the model of success

- told in the language of business, and the tone of that language was always wildly ambitious

One of the purest expressions of this myth happens to be on a blog: “Although I am jotting down things I read from here and there, I am not too certain of the actual dates these events took place, but if it wasn’t for these events in the first place, Winnipeg might still be a thriving metropolis. Thanks alot history.” Acme, “Winnipeg Was Once Chicago of The North” (2007).

This myth built the buildings in the Exchange District and the mansions on Wellington Crescent. It is why we have a railway marshalling yard downtown.

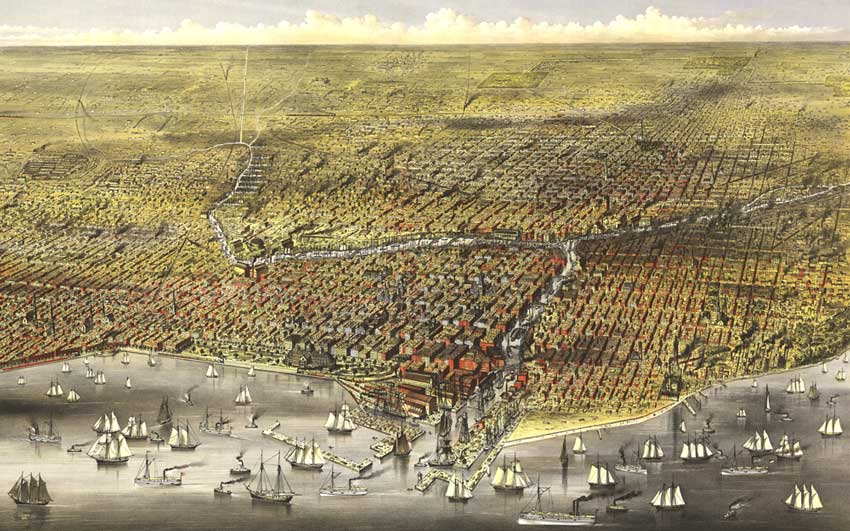

Conventional wisdom says this myth evaporated with the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914.

Winnipeg was never a rival to Chicago.

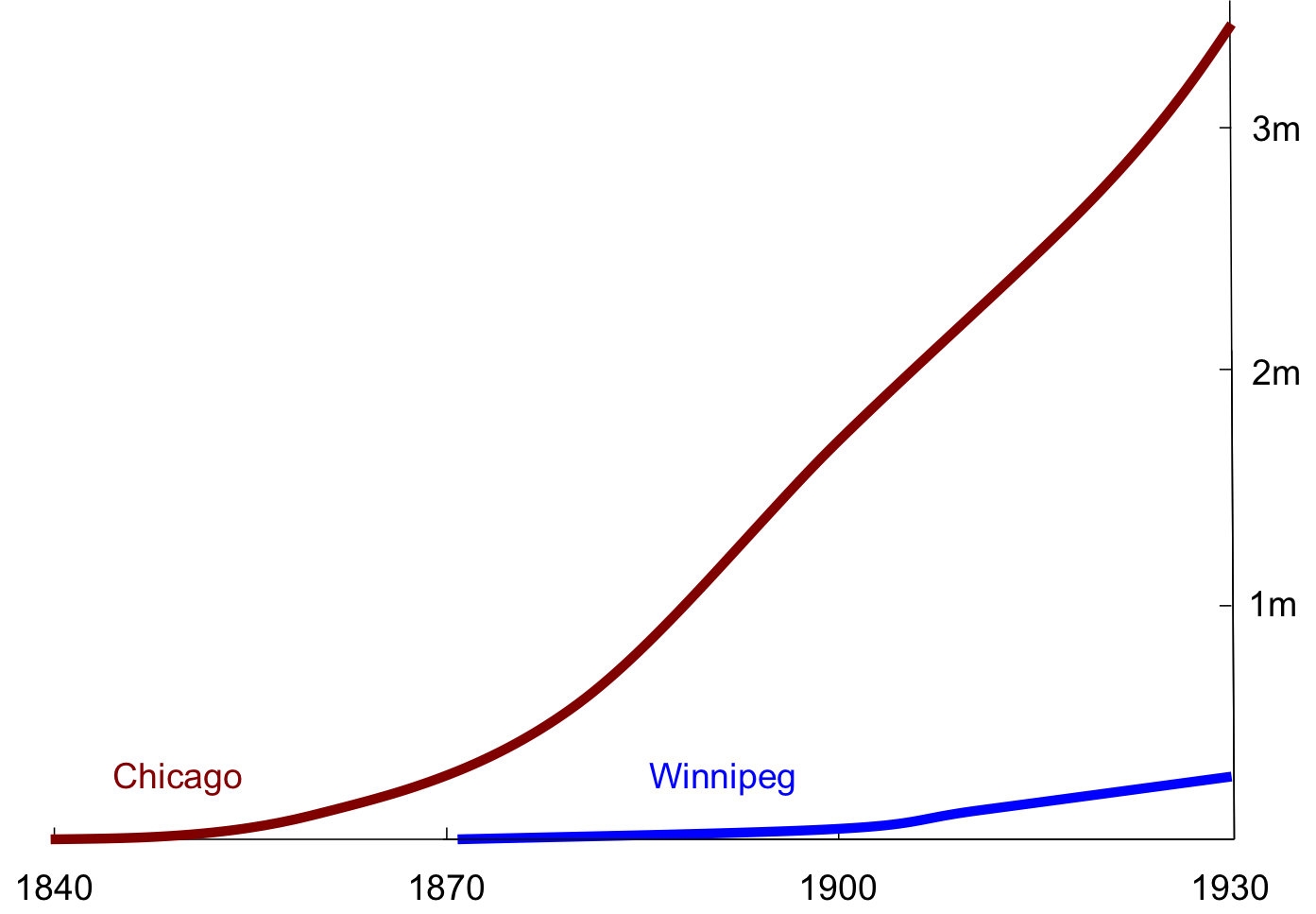

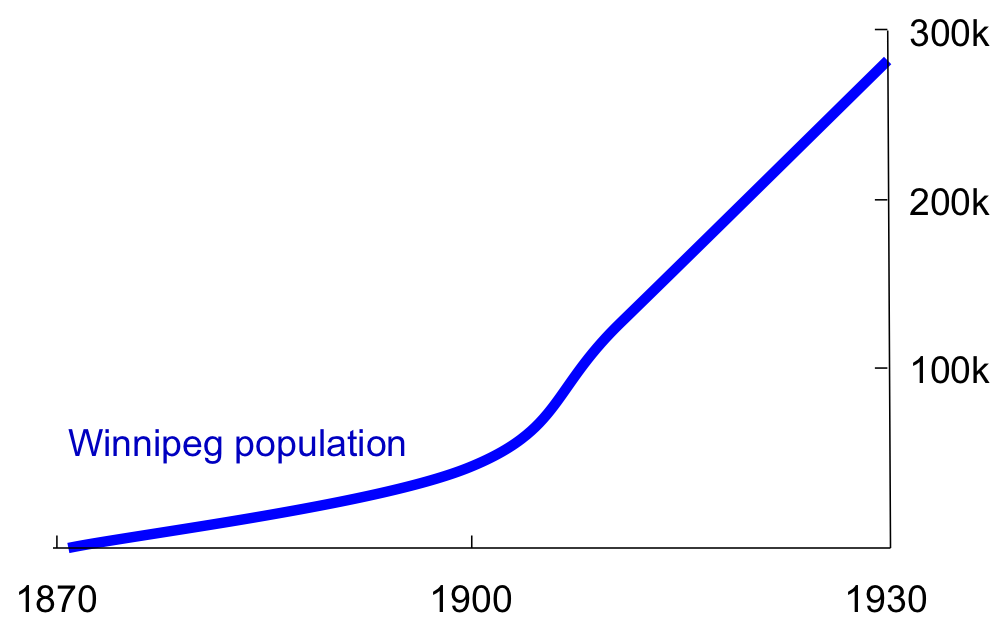

Granted, Winnipeg underwent significant, sustained population growth for 60 years after it was founded. (Note how this growth isn’t interrupted by the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914.)

But Chicago had a 30-year head start, and was always orders of magnitude bigger than Winnipeg.

But Chicago had a 30-year head start, and was always orders of magnitude bigger than Winnipeg.

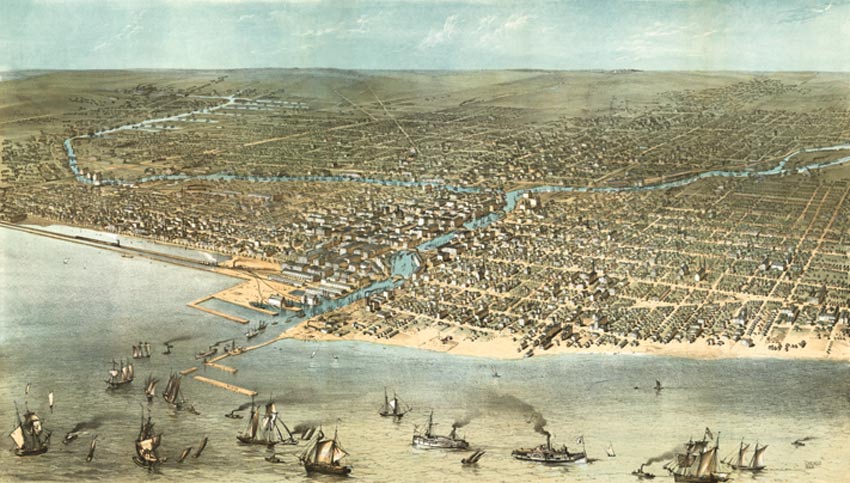

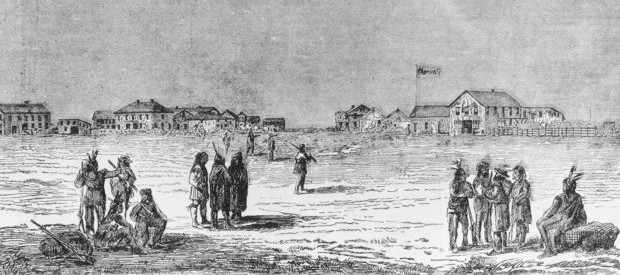

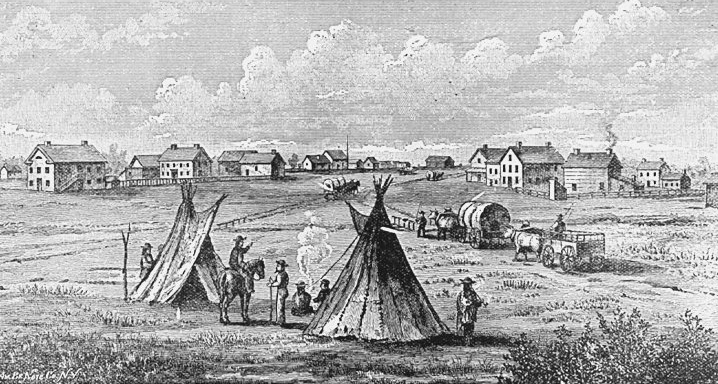

This difference between the two cities was obvious in contemporary drawing, in maps, and in photographs.

It would have been more than obvious to anyone spending even a day or two in both cities.

Chicago 1868 Chicago 1874 |

Winnipeg 1869

|

Lately, we’ve transferred our external reference from Chicago to Calgary. But the looming sense of inadequacy is still with us.

This is a delusional, toxic myth. “Chicago of the North” is our Casablanca. It drowns out the reality. It makes us feel that Winnipeg used to be a more ambitious city than it is now, that the Chicago-of-the-North period the high-water mark, that our best days are behind us.

Myths endure, even as their meaning changes. New York shape-shifts in our imaginations with each movie. With Chicago-of-the-North, what was originally a myth of ambition has transformed into a myth of failure. “We used to be important” mutates almost inevitably into “we are a failure now”.

1919

The myth closest in time to Chicago-of-the-North, yet completely different in character, is the 1919 Strike. The Strike split the city between north and south. The dividing line—the Assiniboine River—is still the line that divides rich and poor neighbourhoods.

All histories of Winnipeg spend a lot of time on the Strike. Not this one. Two highlights.

First: What was this conflict about? Usually, it’s framed as a contest between left and right. It’s also useful to understand that it was a conflict between ethnic groups. The Anglophone leadership in the city had aggressively pursued immigration from eastern Europe, in part to drown the Francophone majority, who dominated 50 years earlier. To the Council of 1000, the Strike suggested that this strategy had backfired, that they’d solved one problem, only to create a bigger one.

Second: The violence. There was, of course, what you might call “conventional violence”. The specials and the mounted police charges—these were standard techniques of the time to put down labour unrest. What is distinctive about the Winnipeg Strike is the militarization of the response.

This is an echo of the how the Red River Rebellion was handled—a military response to a civic conflict.

Red River Rebellion

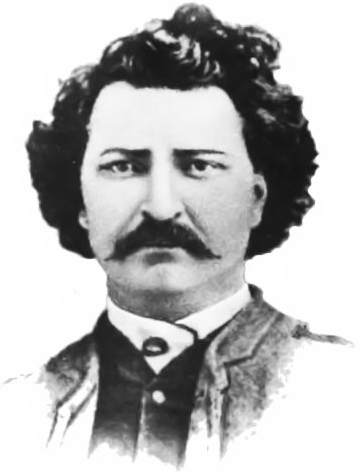

Louis Riel functions as a nearly perfect mythic figure. He is a field on which to play out the contests for the meaning of our history—for self-definition, for the contemporary distribution of power. He gets pulled like taffy between Francophone, Metis,

Louis Riel functions as a nearly perfect mythic figure. He is a field on which to play out the contests for the meaning of our history—for self-definition, for the contemporary distribution of power. He gets pulled like taffy between Francophone, Metis,  and everyone else who feels they have a stake in the history of this place.

and everyone else who feels they have a stake in the history of this place.

Everyone has a Riel narrative. Here is mine:

There were two Riel rebellions. The first one here in 1869, and the second one in Saskatchewan in 1885. They were not the same rebellion. It is possible to see the second rebellion as a contest between Metis and Canada. By 1885, Riel was already functioning as a mythic character, as a figure put forward into the public arena for his symbolic power. I might even say he was executed because he was already mythological. But he was not mythological in the first.

By the mid-1800’s, the Winnipeg area was a rich cultural stew—a Metchif speaking majority, but with plenty of Scots, Francophones, and aboriginal people. If we applied modern terms onto that community, we’d call it multicultural, with a Metis majority.

New settlers came from Ontario in the 1860s. They were determined to have Manitoba join Canada—as an anglophone province. They identified themselves as the Canadian Party.

In their ambition and eastward focus, they prefigure the Chicago of the North advocates of 40 years later.

Riel and the Metis leadership put together a series of conventions from November 1869 to February 1870. Riel was determined to bring together all the different groups of the area.

Agreement was not easy, but they did finally hammer out terms that virtually every group accepted (except the Canadian Party, of course). And it was those agreements that formed the basis of Manitoba’s entry into Confederation.

Riel’s recognition of the multiple nature of Winnipeg was prescient. He understood the challenge which would underpin virtually every Winnipeg myth-event of the next 150 years—the reality of (primarily ethnocultural) differences, and the desire to bridge them.

Riel was attempting to build the Winnipeg that we are still struggling to create.

The JJ Harper Shooting

The focus here is not Mr. Harper as a person, but on what the shooting came to symbolize about our city—not to the outside world, but to ourselves.

The focus here is not Mr. Harper as a person, but on what the shooting came to symbolize about our city—not to the outside world, but to ourselves.

Before the shooting, we wanted to see ourselves as a modern, tolerant city.

The third conflict-based myth of Winnipeg was the JJ Harper Shooting. Harper was shot by a Winnipeg police officer in 1988. It gripped the city. The shooting and its aftermath threw that self-image into question. We were not as peaceful—not as whole, not as healthy—as we imagined.

This mythic event had a measurable effect—in buildings, in who we include in civic rituals, in the attention being paid to aboriginal Winnipeg—that was not here 30 years ago. We do not know if this will “work”, if we can truly become a single city. It is, however, the enterprise we are engaged in now.

The North End

Not every Winnipeg myth is about either failure or conflict.

It is hard for us to remember how poor the North End was 100 years ago.

[photo]

This could easily be Ireland or Poland of exactly the same time. In part because of outbreaks of disease, the rest of the city saw the North End as a dirty place. A foreign place. A danger. Exactly as American Know-Nothings had reacted to foreignness 50 years earlier. For those south of the Assiniboine, the North End was the unknown country.

Within the North End, however, a different idea of itself took hold. People began to see themselves as creating a multiple world of multiple origins and multiple ideas. It was confined to the North End enclave but, within that, an urban place.

If we were to (again) impose contemporary language backward onto the North End of 80 years ago, we would call it a multicultural place. The North End was recreating the community that nearly took hold 80 or 90 years before, in the Red River Rebellion.

See: John Paskievich and Stephen Osborne, The North End (2007) and John Paskievich and Michael Mirus, Ted Baryluk’s Grocery (1982).

Don’t think for a moment that the North End was as halcyon a place as nostalgia would have us believe. To claim immigrants left behind every single conflict and struggle in the “old country” the moment they landed in Winnipeg…it is not believable. But the powerful mythology of a peaceful, multi-ethnic community still endures today.

The Flood

The flood of 1950 is remembered as a city-wide communal experience. What tends to get lost in the telling is that, physically, the water won and the human beings lost. But psychically, the flood was as positive for Winnipeg as the 1919 Strike was negative. It took the language of the North End—of everyone working together despite their differences—and applied it to the entire city.

Unicity

In the 1960s, our leadership used the centenaries of Winnipeg, Manitoba and Canada to redefine Winnipeg. The Perimeter took shape. The floodway was built. Eleven enclaves got amalgamated into a single municipality—Unicity. The ConcertHall/MTC/Museum/CityHall/PublicSafetyBuilding complex got made. We re-used elements of the Chicago-of-the-North myth (not the visuals—the ambitions) to serve a Regenerator project: a single, confident, modern Winnipeg.

The attempt failed. Forty years on, these buildings do not gather the whole city together. Their exteriors shun pedestrians. The Public Safety Building’s windows are reminiscent of nothing so much as gun turrets. The unintended speech of these buildings—of exclusion and intimidation—has drowned out the intended speech—that we are a modern, urban place.

There was, however, another attempt at the same action going on at the same time. Folklorama began as a Manitoba centennial project. Winnipeggers gripe about the crowded venues and the amateur entertainment, but this ethnocultural festival endures. Folklorama succeeds because it takes the mythology of the North End enclave—of diversity, happy together—and expands it to the city as a whole. It achieves the ambitions of Unicity, where the buildings could not.

The Forks

“Located at the junction of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers, the Forks has been a gathering place for over 6,000 years.” So says Parks Canada and more than 100 other websites, who all cite it as fact. The-Forks-as-gathering-place is now one of the dominant stories about Winnipeg.

And yet…

6,000 years ago, the Red and Assiniboine rivers didn’t even meet; the Assiniboine drained into Lake Manitoba. About 4,000 years ago, the Assiniboine drained through the La Salle River’s channel and the “confluence of the Red and Assiniboine” was 15 km south of the Forks. Sometime between then and 2,500 years ago, it met up with the Red at what we now call the Forks.

“…the Assiniboine River …drained into Lake Manitoba from approximately 7,000 BP to 4,500 BP….The Assiniboine has flowed into the Red River since 4,500 BP but has followed several different routes, many of which did not terminate at the modern Forks. By about 3,000 BP, the Assiniboine River drained through the La Salle channel and joined the Red River 15 km south of Winnipeg. The river returned to the Forks some time before 2,450 ± 80 yr. BP (BGS-1635) and had established its entire modern channel sometime after 700 BP.” Nielsen, et al. (2002)

This isn’t news.

- Twenty-five years ago: Rannie, W.F., 1999 “A geomorphological perspective on the antiquity of the “Forks” Manitoba Archaeological Journal, Vol. 9 (1): 103-113.

- Thirty-five years ago: Rannie, W.; Thorleifson, L.H.; and Teller, J.T. (1989) Holocene evolution of the Assiniboine River paleochannels and Portage la Prairie alluvial fan, Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 26(9): 1834-1841.

You might say: So it’s only 3,000 years. Just an exaggeration.

Problem is, where the rivers meet only matters if you travel by river. On the plains, aboriginal people followed the buffalo, and buffalo travel overland more often than they swim up and down the river. For a few years during the fur trade, “where the rivers meet” mattered. But, by the time Winnipeg was founded, where the river met the railway mattered more. [picture] Point Douglas was the centre of town; the Forks was an afterthought.

Yet the myth of the Forks is a magnetic force, aligning roads and buildings, attracting money, attracting people, focusing attention. Why?

The Forks is a physical space, but it is also a field of contest.

The modern Forks is roughly 25 years old, yet debates over it have been frequent and hot. We have fought over its commercialization, greenspace, subsidies, ballpark, Esplanade, and Canadian Museum of Human Rights.

Fighting over the Forks has been a way to fight over what we are as a city. Unicity aspired to define Winnipeg. Even if that project failed, the desire for definition did not disappear. The Forks has become the physical embodiment of that desire.

The Forks myth works, not because it is accurate, but because it speaks Winnipeg as a Regenerator’s city: a shared, peaceful, urban space.

Seeing Myths Together

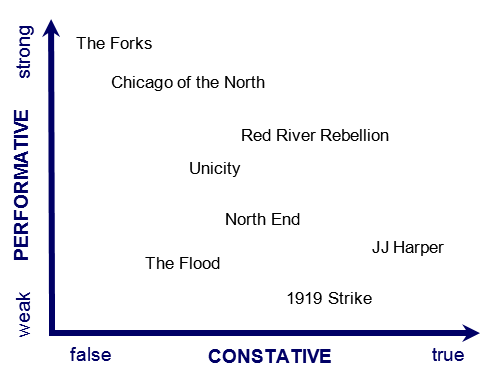

It would be easy to range these mythologies over performative and constative space:

Interesting, but of little use. Analysis qua analysis will not answer our third question. Our agenda is applied mythology.

3. How Can This City Be Changed?

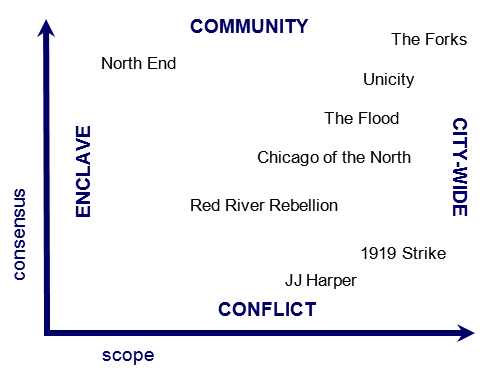

To be useful, we must range our mythologies across the two-dimensional grid of consensus and scope:

Why is this consensus/scope grid useful? It can serve as a map of narratives, showing where they align, and how they compete.

These mythologies and this grid are particular to Winnipeg, but the technique is not. Urban mythologies are performative speech acts which enter the public field and contest for dominance. A city’s built physical space—it’s nouns—is the record of this contest.

This contest of myths operates below the surface of public discourse, but is more powerful than the rational and the explicit.

In the construction of a city, myth is more powerful than any cost-benefit analysis.

5 Principles of Urban Mythology

- myths are fluid

- (even false) myths endure

- myths align

- myths compete

- unexamined myths can bite you

Consider Winnipeg and its recent history: Why were the opponents to the MTS Centre not able to stop it? Why have the critics of Waverley West been unable to get traction?

Those who lost those contests will claim it was “money” and “politics”. Those who won will claim “planning” and “public support”. These are all only symptoms.

The advocates of these projects linked them to extant urban mythologies particular to Winnipeg…and their opponents did not.

For those wanting to make change, I offer four tools:

4 Principles of Applied Urban Mythology

- do it yourself

- face facts

- connect facts to myths

- fight myths with myths

Sources

Acme. “Winnipeg Was Once Chicago of The North.” In Rants. OurRant, January 18, 2007. http://ourrant.ca/main/acme/2007/01/18/winnipeg-was-once-chicago-of-the-north/ (accessed August 3, 2008).

Allen, Woody and Marshall Brickman, writers, Woody Allen, direction. Manhattan. United Artists, 1979.

Austin, J. L. How To Do Things With Words, second edition, ed. J. O. Urmson and Marina Sbisà. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1975. Originally delivered as the William James Lectures, Harvard, 1955.

Barthes, Roland. “Semiology and Urbanism.” In The Semiotic Challenge, trans. Richard Howard, 191-201. New York: Hill and Wang, 1988. Originally delivered at a colloquium at the University of Naples, 1967.

Centre for Environmental Design Research and Outreach. “Forks Urban Revitalization Project.” In CIP/ACUPP Case Study Series. Calgary, AB: ca. 1996. http://www.ucalgary.ca/ev/designresearch/projects/2001/CEDRO/cedro/cip_acupp_css/forks.html (accessed August 9, 2008).

Clark, Lovell. “Schultz, Sir John Christian.” In Dictionary of Canadian Biography; Volume XII, 1891 to 1900, ed. Francess G. Halpenny. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, Les Presses de l’université Laval, 1990.

Cook, Ramsey. The Regenerators: Social Criticism in Late Victorian English Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1985.

Derrida, Jacques, “Signature Evénement Contexte.” In Margins of Philosophy, trans. Alan Bass. Originally delivered at the Congrès international des Sociétés de philosophie de langue francaise, Montreal, August 1971.

Eco, Umberto. A Theory of Semiotics. London: Macmillan, 1976.

Epstein, Julius J., Philip G. Epstein, Howard Koch and [uncredited] Casey Robinson, screenplay, Michael Curtiz, direction. Casablanca. Warner Brothers Pictures, 1942.

Folk Arts Council of Winnipeg Inc. “About Folklorama.” Winnipeg, MB: n.d. http://www.folklorama.ca/48 (accessed August 8, 2008).

Foote, L.B. (?), “Winnipeg Riot: Armoured Cars.” Archives of Manitoba/Archives du Manitoba, Winnipeg Strike 34, N12321 Year: 1919. http://manitobia.ca/content/en/photos/events/WSC_1919_0621_N12321.xml (accessed March 23, 2015).

Hamm, Sam, and Warren Skaaren, screenplay, Tim Burton, direction. Batman Warner Brothers Pictures, 1989.

Heritage Winnipeg. “The Exchange District.” Winnipeg, MB: Heritage Winnipeg, n.d. http://www.heritagewinnipeg.com/historic_exchange.htm (accessed August 6, 2008, link no longer active).

Hutchison, Bruce. The Unknown Country: Canada and Her People. Toronto: Longmans, Green & Company, 1942.

JamesK, et al. “Winnipeg vs Calgary.” In Forum. Winnipeg, MB: Topix LLC, 2008. http://www.topix.com/forum/ca/winnipeg-mb/TM9CLJDR03F94828T (accessed August 4, 2008).

Nielsen, E., St. George, S., Matile, G., and Keller, G. 2002. Environmental geoscience in the Red River valley. CPG/NGSC field trip guidebook. 2002 Energy and Mines Ministers’ Conference, Winnipeg, Manitoba, September 14, 2002. http://www.manitoba.ca/iem/geo/pflood/p_pdfs/envirogeosci_mb.pdf (accessed March 23, 2015).

Parks Canada. “The Forks National Historic Site – Scolaires-School.” n.d. http://www.pc.gc.ca/eng/lhn-nhs/mb/forks/edu/Scolaires-School.aspx (accessed March 23, 2015).

Paskievich, John, photography, Michael Mirus, direction, Ted Baryluk’s Grocery. Winnipeg, MB: National Film Board, 1982.

Paskievich, John, photography, Stephen Osborne, introduction. The North End. Winnipeg, MB: University of Manitoba Press, 2007.

Rannie, W.F., 1999 “A geomorphological perspective on the antiquity of the “Forks” Manitoba Archaeological Journal, Vol. 9 (1): 103-113.

Rannie, W.; Thorleifson, L.H.; and Teller, J.T. (1989) Holocene evolution of the Assiniboine River paleochannels and Portage la Prairie alluvial fan, Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 26(9): 1834-1841.

Reinach, Adolf. “Die apriorischen Grundlagen des bürgerlichen Rechtes.” In Jahrbuch für Philosophie und phänomenologische Forschung 1 (1913): 685-847. Trans. J. F. Crosby, as “The Apriori Foundations of the Civil Law.” Aletheia 3 (1983): 1-142.

The Frontier Centre for Public Policy. “Winnipeg’s Property Taxes.” In Notes from the Frontier Centre for Public Policy. Winnipeg, MB: The Frontier Centre for Public Policy, April 7, 2001. http://www.fcpp.org/main/publication_detail.php?PubID=104 (accessed July 30, 2008).

The Manitoba Centennial Centre Corporation. “History of the Manitoba Centennial Centre.” In About Us. Winnipeg, MB: 2004. http://www.mbccc.ca/au-history.asp (accessed August 4, 2008).

Unilever. The Axe Effect. n.d. http://www.theaxeeffect.com/axeeffect.html (accessed August 1, 2008).

Sir John Christian Schultz, Canadian Pary

Sir John Christian Schultz, Canadian Pary